Longevity Doctors Challenges

Issue 70: The front page of longevity medicine - curated by doctors, for doctors.

Hey Doc,

I know the newsletter usually lands on Sunday, but last week I was on the road.

Miami, Palm Beach, Boston. Meeting doctors where they practice, seeing their world, listening. I took a moment to step back, process, and reflect.

The conversations were real, docs shared their challenges and I want to share them with you.

Here we go.

Dr. David Luu - Founder, longevitydocs.™

Each week, I try to explore one idea that could advance longevity medicine and hopefully support physicians in bringing it to life.

10 Core Challenges Longevity Doctors Are Facing Right Now

Last week, I met with 25 physicians passionate about evidence-based longevity medicine. What I heard wasn’t about the promising interventions, it was about the reality of building a new field from scratch.

Here’s what’s keeping them up at night:

1. Patient Understanding & Expectations

Patients arrive armed with acronyms (NAD, GLP-1, VO₂ max) but lack understanding of foundational principles. Most still expect insurance coverage for preventive optimization, creating friction before care even begins.

2. Trust & Credibility

The field is flooded with influencers, wellness entrepreneurs, and practitioners of varying credibility. Patients can’t easily distinguish evidence-based medicine from expensive pseudoscience, and serious physicians bear the reputational cost.

3. Standard of Care & Clinical Protocols

Little consensus exists on which biomarkers matter, what testing sequence makes sense, or which interventions have sufficient evidence. Every clinic is creating its own playbook.

4. Access & Affordability

Annual programs range from $100 to $250,000. Most doctors entered medicine to help people, not to serve exclusively the ultra-wealthy. They’re searching for scalable models that expand access without compromising quality.

5. Clinic Identity & Positioning

The transition from “treating disease” to “optimizing healthspan” requires entirely new language. Doctors trained in pathology now need to articulate value propositions around performance, prevention, and delayed decline.

6. Pricing, Packaging & Scale

Should you charge per test? Per visit? Annual retainer? How do you grow without becoming an absentee physician or hiring inexperienced providers? No established business model exists.

7. Team Recruitment & Training

Finding staff who understand advanced diagnostics, can interpret complex biomarker panels, and deliver premium patient experiences is nearly impossible. Training programs don’t exist. Retention is a constant challenge.

8. Regulation & Compliance

Off-label prescribing, novel diagnostics, cash-pay models, and interstate telemedicine create a minefield of legal and regulatory risk. Most doctors are navigating this alone, without clear guidance.

9. Research Participation

Physicians want to contribute to the evidence base, not just consume it. They’re generating real-world data daily but lack infrastructure to participate in meaningful research or registries.

10. Tech & AI Literacy

Wearables, multi-omics, continuous glucose monitors, AI diagnostics: the tools are proliferating faster than clinical understanding. Doctors want practical training, not vendor pitches or hype cycles.

Longevity medicine is still in its early stage and that’s the opportunity.

We are building this field in real time. The clinical standards, the operational models, the regulatory frameworks, the education, none of it exists yet at scale. And that’s exactly why physicians feel both excited and cautious.

What I heard this week is simple: doctors want to practice good medicine, expand access beyond the ultra-wealthy, and build something sustainable. They want to enjoy their work again.

Every week, the Longevity Docs WhatsApp group feels like a front-row seat to the future of medicine. Here’s what had doctors buzzing:

Are we ready for AI-powered clinics?

What the docs discussed:

Using NotebookLM, ElevenLabs, custom agents, and podcast-style explainers for patients.

Building RAG models for clinics using the Google Gemini File Search API.

Setting up HIPAA-compliant hosting (Google Cloud + BAA).

Deploying HIPAA-safe voice agents using ElevenLabs & VAPI.

Exploring digital twins, patient-facing AI explainers, and AI-driven clinical workflows.

The challenge of connecting patient data across time (LDL 2014 vs LDL 2024) inside RAG.

Real-world barriers: HIPAA for phone calls, model training, reliability, and security.

Emerging norm: every clinic will need AI search, AI communication, and AI documentation tools.

Monday takeaway:

The consensus is clear: every clinic will soon need AI tools the same way they rely on EHRs today. Physicians now have a window to experiment with these tools: to simplify their workflow, reduce administrative load, and spend more time on real clinical care.

Are Mitochondrial Testing Legit?

What the docs discussed:

Agreement that mito dysfunction is real — but testing needs context, not reflex ordering

Debate on when to introduce mito or membrane testing in a patient pathway.

Concern that these tests may be too advanced for patients who haven’t mastered basics (sleep, nutrition, training, stress).

Need for clear interpretation frameworks, not just reports.

Growing interest in using these tests to explain non-responders and plateau cases.

Monday takeaway:

Mitochondrial and membrane tests are still early-stage and need stronger validation. They’re not step-one diagnostics, they belong in tier 2–3, once fundamentals are dialed in and a patient isn’t improving. These tools must prove real outcomes and show clear links to evidence-based interventions. Until then, they’re best used as exploratory or research tools, not prime-time clinical diagnostics.

VO₂max matters

What the docs discussed:

Treadmill testing generally produces higher VO₂max than cycle ergometers.

Most patients never reach a true VO₂max during testing. Even elite athletes rarely do.

The biggest healthspan gain comes from moving patients out of the lowest fitness quartile, not chasing elite VO₂ numbers.

Debate on whether VO₂max is the cause of longevity benefits or simply a marker of lifestyle inputs (weekly training volume).

A fit person with a VO₂ of 50 may be healthier than an untrained person with a 60.

High VO₂max at the extreme may come with AFib tradeoffs in endurance athletes.

An omics-based non-exercise VO₂max estimate is in development could be a more practical “biological fitness” metric.

Monday takeaway:

Precise VO₂ testing is useful, but the real intervention is still consistent training. The biggest longevity return comes from making the unfit moderately fit not from chasing peak VO₂ numbers.

Not a member yet? Join the debate in the WhatsApp group

Longevity Docs is a highly vetted, invitation-only community for physicians shaping the future of longevity medicine. Apply to connect with our team.

Each week, I highlight studies that could shape the future of longevity medicine. This week is very cardio focused

DECAF Trial (Coffee Consumption & AFib)

This randomized trial published in JAMA shows that coffee is not proarrhythmic in fact, drinking one cup of caffeinated coffee per day reduced AF recurrence from 64% to 47% after cardioversion.

The hazard of recurrence dropped by 39%, with no safety concerns and no difference in adverse events.

For decades, patients with AF have been told to avoid caffeine, this study suggests the opposite may be true.

For Longevity Docs, it reinforces a bigger theme: evidence > dogma, and lifestyle guidance must evolve with latest data.

Evolocumab in Patients without a Previous Myocardial Infarction or Stroke

This NEMJ study shows that evolocumab prevents first cardiovascular events, not just recurrent ones.

In patients with atherosclerosis or diabetes but no prior MI or stroke, PCSK9 inhibition cut major events by 25% and had no safety penalty.

For prevention-first medicine, this confirms that aggressive LDL lowering might be effective before a crisis ever happens.

For Longevity Docs, it strengthens the case for early detection, early lipid control, and moving cardiology from reaction to prevention.

The Lancet Commission on rethinking coronary artery disease: moving from ischaemia to atheroma

This new Lancet Commission reframes heart disease entirely: not as a late-stage emergency, but as a lifelong atherosclerotic process we can detect and treat decades earlier.

The future is early imaging, early biomarkers, and aggressive prevention long before ischemia appears.

For longevitydocs., this is the mandate: lead the global shift from treating events to eliminating advanced coronary disease altogether.

Every week, I track funding, FDA approvals, product launches, and breakthrough announcements shaping longevity medicine.

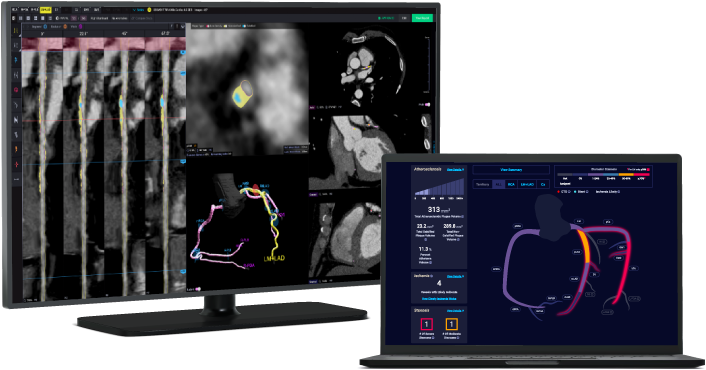

AI CT Scan Reimbursed: Prevention Just Became Billable

A new STAT article confirms that Medicare will now reimburse $1,000+ for AI-powered coronary plaque analysis (HeartFlow, Cleerly, Elucid, Caristo), with private insurers set to follow. This moves plaque quantification from a concierge add-on to a mainstream reimbursed pathway.

Takeaway for Longevity Docs: Preventive cardiology is now insurable. Early plaque detection, soft-plaque analysis, and longitudinal tracking finally have reimbursement codes.

FDA Will Regulate AI therapy

The FDA is preparing to regulate AI mental-health tools built on large language models, evaluating whether they should be prescription-only, adolescent-approved, or classified as medical devices.

Takeaway for Longevity Docs: AI in healthcare is moving into a regulated era. Clinics building agents, explainers, and RAG tools will need compliance and HIPAA-safe systems. This raises standards and rewards serious clinicians over hype-driven platforms.

Gene-Edited Babies? Yes and Sam Altman is funding it.

A Times investigation reveals that Sam Altman is backing Preventive, a startup aiming to gene-edit embryos to eliminate hereditary disease. They’ve raised $30M and are scouting countries where edited embryos could legally become live births.

Takeaway: The future of prevention is shifting toward pre-life design. Gene editing, CRISPR diagnostics, and embryo screening will converge - demanding ethics, restraint, and strong clinical leadership to avoid techno-utopian extremes.

Longevity Docs Table: Miami and Boston - LA, SF, Vegas are next

We launched the Table because physicians told us they felt isolated and needed guidance to transform their practice. Each intimate, Jeffersonian-style dinner gathers a curated circle of longevity-minded physicians to share real challenges and breakthroughs, tackling questions no conference can answer.

Miami and Boston were great Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas

Where to Find Us

Novato · Dec 6-8 – Longevity Clinic Roundtable

Las Vegas · Dec 12-13 – A4M Conference

Las Vegas · Jan 6-9, 2026 – CES

New York · January 31 – Longevity Docs AI/Tech Mastermind

Cannes, France · June 9-11, 2026 – Longevity Docs Summit

Longevity Docs is a global education and community platform uniting physicians to make longevity medicine the new standard of care.

With members in 50+ countries, we democratize longevity medicine by giving doctors access to a trusted community, rigorous education, and culture-shaping platforms.

Our mission is to equip physicians with the knowledge, tools, and network to confidently practice evidence-based longevity care. We do this through three pillars:

Community: connecting physicians worldwide into a curated and collaborative network.

Education: providing evidence-based training, certification, and innovation.

Culture: bringing longevity medicine into the scientific and cultural mainstream.

Subscribe to the Longevity Docs Newsletter

Stay connected with a global network of 500+ physicians in 50+ countries advancing longevity medicine. Get evidence-based insights, clinical updates, and exclusive access to the community shaping the future of longevity care.

Newsletter Disclaimer:

This is such a needed reality-check! “Longevity medicine” isn’t hard because the science is uninteresting; it’s hard because the clinic is where complexity shows up: heterogeneous patients, imperfect evidence, long time horizons, and a lot of commercial noise. From a physician scientist’s perspective, the central challenge is translating probabilistic risk reduction into decisions that still feel human and ethically grounded. We’re often working with (1) endpoints that take years to manifest, (2) surrogate markers that can be gamed or overinterpreted, and (3) interventions whose benefit depends heavily on adherence, environment, and socioeconomic constraints. That makes the job less about finding a magic protocol and more about building a thoughtful system: prioritizing fundamentals, personalizing what truly needs personalization, and being transparent about what we know, what we suspect, and what we don’t yet know.

I also appreciate the implied tension you’re naming: patients want certainty and optimization, while good medicine demands humility, shared decision-making, and attention to harms (over-testing, incidental findings, anxiety, cost, opportunity cost). The clinicians who do this well are the ones who can hold both, ambition and restraint, at the same time.

The ten challenges you outlined resonate deeply, especialy the tension between wanting to expand access and the current economic realities of cash pay models. The point about physicians building their own playbooks in absense of clinical consensus is particularly telling. Its encouraging to see the DECAF trial challenging old dogma about coffee and AFib, and the Medicare reimbursment for AI CT scans feels like a tipping point for prevention becoming mainstream rather than concierge only.